Photo: Momoko Nakamura

Photo: Momoko Nakamura

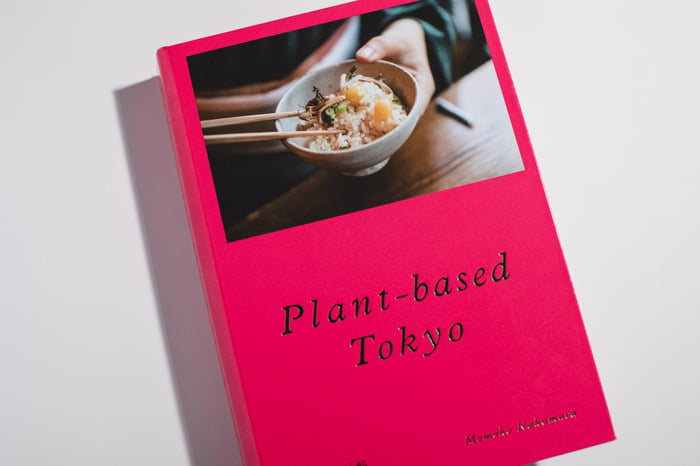

For most of us, there are four distinct seasons: spring, summer, autumn, and winter. For Japan however, the traditional Japanese calendar divides the year into 72 micro seasons. For Momoko Nakamura, author of Plant-based Tokyo, eating vegan in Japan means eating what is offered during each micro season.

“In Japan, it’s about the season and our connection with nature. It’s about our relationship with the flora around and how we’re experiencing that season.”

See also: A vegan guide to Hong Kong

Photo: Sunil Naik

Photo: Sunil Naik

See also: How Woodstock Farm Sanctuary gave 5000 farmed animals a new home

This philosophy is expressed in her book and shapes the way she views veganism in Japan. We caught up with Nakamura to learn more about her work, Japan’s plant-based movement, and how rice should move like waves in the sea while cooking.

Could you share with us a bit more about your book, Plant-based Tokyo?

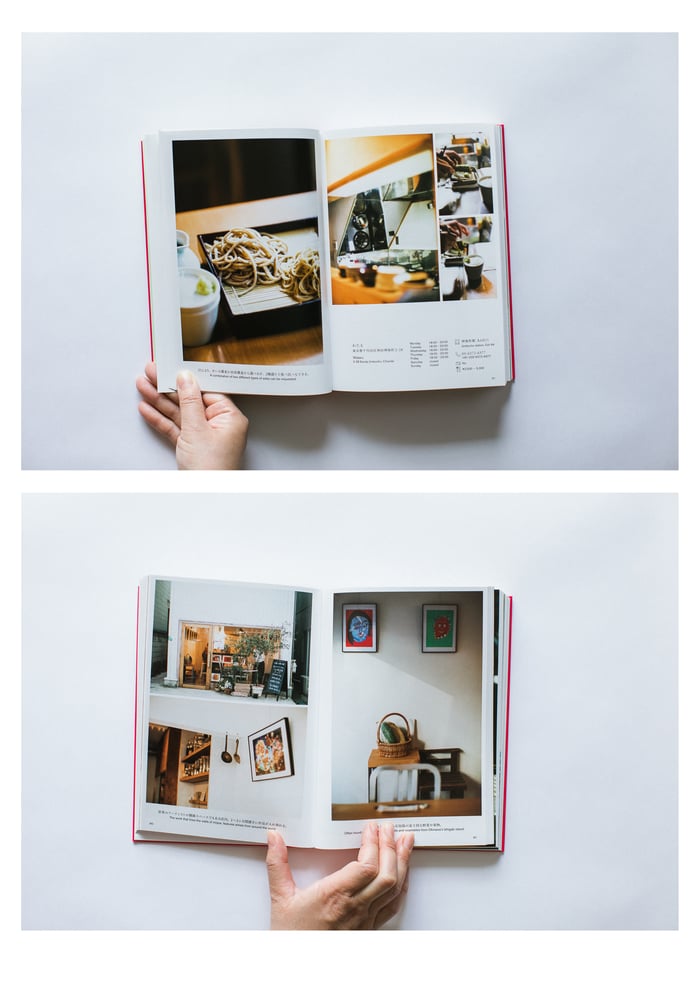

Plant-based eating in Japan is what eating is in Japan. Japan is incredibly seasonal, which is the fundamental philosophy behind Plant-based Tokyo. It is conversations with or mini-biographies of plant-based chefs throughout Tokyo, understanding what they think, who they work with, and how they work with their hands, the tableware that they use, the farmers they work with, and the fermenters they work with — who are all the people, places and things that pass through their work as they're creating their piece of art, which is the food on the plate. So what each of them do is essentially work in rhythm with the micro seasonal calendar.

Photo: Momoko Nakamura

Photo: Momoko Nakamura

Tell us more about the selection of chefs – was there a certain profile that you were looking for, and why?

It's not just people making vegan food, but I specifically chose chefs working in rhythm with the micro seasonal calendar. Then, we as the diners can benefit from the work they do because the vegetables, grains, or the legumes of that season are the ripest, and we can enjoy them at their peak.

For example, a tomato made by nature is warmed by the sun, and it feeds from the rain. But so many tomatoes are made in greenhouses. That allows you to eat tomatoes midwinter, but when they're not actually in season. If they're not absorbing nature's rhythm of the sun and rains and are in a boxed-off environment, then we're not on the receiving end of the deliciousness in a tomato that has been part of this natural rhythm.

In my opinion, the chefs who think about the micro seasons and are aware of them and can incorporate them into their work make the most delicious food.

What’s a common misconception people have about veganism in Japan?

I think the misconception is that if you're strictly vegan, you're probably thinking, do I want to eat this broth, for example. Broth in Japanese is dashi, a word commonly used around the world. But dashi can mean many different things; depending on the region of Japan, the type of dish you want to create lets you make different dashi.

So even in western cooking, sometimes you want to use a beef broth, but then sometimes you want to use veggie stock for something else. It’s the same thing. Sometimes you want to use a sea vegetable-based broth like a Kombu-based broth. Sometimes you want to do a combination of Kombu and mushroom.

I think the misconception is that dashi equals animal products, but there’s plenty of different dashi types made using sea vegetables, plants, and mushrooms.

A lot of people don’t strongly associate Japan as a particularly vegan-friendly country. Are there any interesting trends to take note of?

I think the trend is color because Japanese people say, we eat with our eyes. Also, with your eyes, you're able to recognize the season. For example, if you see lighter shades, like mint greens, yellows, and whites, then you know that you are in the early parts of spring. And so, depending on the color palette, you can feel that season. Every season is colorful, but a different shade of color.

Photo: Momoko Nakamura

Photo: Momoko Nakamura

In Japan, one type of eating is Teishoku, meaning one tray with different dishes. So essentially, on one tray, you can see the season's colors. I think it's also the growing number of people who want to post photos on abillion or their social media, wanting to take a picture and share with their friends. It's more enticing to see it colorful.

It's like the rebirth of Teishoku. Teishoku used to be old school. It's a thing with rice and miso soup, and with a few side dishes, and that's it. But it's like, there's this new kind of love and renewal for Teishoku. Because it can showcase the assortment of colors, you know? And instead of having one dish, it's almost like a painting. And you can have all these shades and flavors in one tray.

Adding onto the previous question, are there any trends based on different generations in Japan?

There's definitely a younger demographic entering the plant-based conversation. But then, once you start following the thread, you realize Japanese food was always traditionally plant-based. We incorporate a lot of preserved and fermented methodologies into cooking, which is very plant-based and adds a lot of umami flavor to vegetarian dishes. And so, I think Japanese cuisine, in general, is very conducive to delicious plant-based cooking.

Secondly, there's a growing demographic of young mothers who have just given birth. They have never thought about eating well before, but now they have children, so they begin to study cooking and healthy eating.

Then there's a third demographic of an older population, in their 60s, 70s, and beyond, who feel so much better eating plant-based Japanese food. They've gone the steaks and fried chicken route, and now they're back to eating Japanese plant-based food because it feels nice to them, and they can digest it.

Earlier, you went by the name Rice Girl. What was the reason behind this moniker?

For several years, I was working on a project called Rice 100. Initially, it was creating 100 different types of rice blends, meaning different types of rice varietals based on the traditional Japanese micro seasonal calendar.

Every year, I made 24 different types of blends. So for example, in midwinter, I would choose varieties that were dense and mochi-like. For summers, it would be lighter and fragrant, like basmati. I wanted to highlight the breadth and depth of Japanese rice across the country side, and get people thinking about what it means to select rice.

Photo: Momoko Nakamura

Photo: Momoko Nakamura

Rice is the staple of the Japanese table, but many people weren’t thinking about questions like: What am I buying? What am I eating? And so, when people are buying their rice, I want them to think about whether they’re buying organic, which area in Japan are they buying from, what sort of varietal do they want, and will this match to the dishes they want to make during that season? Rice 100 was a project where I was attempting to reconnect Japanese people with their staple ingredient.

What is the best way to cook brown rice?

The best way is with an earthen pot which allows the temperatures to rise very high. It's also shaped to boil in a very exuberant way, and the rice can move. So the rice is not sitting at the bottom but moving in that cradle, which creates a lot of air between the rice grains.

When you don't have a proper cooking appliance, the rice bits get mushy at the bottom or part of the top. When the rice comes to a boil at the beginning, it needs to breathe and dance and move about. A donabe would be a good place to start when cooking rice.

Photo: Momoko Nakamura

Photo: Momoko Nakamura

To cook brown rice, I have a trick of remembering, and that's spring, summer, autumn, and winter.

Spring: At the beginning, you have it on medium heat. Once it comes to a boil, it takes about 10 minutes because it's on medium heat. Then I add a little bit of sea salt, not for flavor but to match the energies of the earth to that of the sea.

Japan is said to be made of mountains and seas because it's an island country. Everything that we do needs to connect and combine the energies of the land and the sea. So when we're making rice, which is an energy of the land, we bring in a little bit of energy from the sea too.

So when the rice finally comes to a boil during springtime on medium heat, I add a little bit of energy from the sea.

Summer: Then I turn it to high heat, which is summertime. Soon, it starts boiling. The rice moves like big waves in the sea, and you let that go for about one minute.

Photo: Momoko Nakamura

Photo: Momoko Nakamura

Autumn: Now, you finally put the lid on for the very first time, and you turn the heat to low; this is autumn. You cook for about 30 minutes and let it be on very low heat for 30 minutes.

Winter: After 30 minutes, you keep the lid. Let it sit for 15 minutes and afterward, you can open and fluff the rice.

Recommend us some of your favorite vegan/vegetarian restaurants in Japan and why so.

I have shared with you one place for dinner, another for drinks, and the third for dessert. Each of the spots are uniquely Japanese, playing to the rhythm of the traditional Japanese micro seasonal calendar, and celebrating the colors, flavors, and textures of the seasons.

Photo: Momoko Nakamura

Photo: Momoko Nakamura